New Late Cretaceous Pterosaur – Eurazhdarcho langendorfensis

An international team of scientists have named and described a new species of Late Cretaceous flying reptile which had a wingspan approximately the same as a Wandering Albatross, but unlike the extant Albatross, this pterosaur lived inland.

Researchers from the University of Southampton (England), in association with the Transylvanian Museum Society in Romania and the Museau Nacional in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil), have identified a new species of azhdarchid pterosaur with a wingspan of around three metres. The fossils were found in Romania (Sebeş-Glod – Transylvanian Basin of north-western, central Romania), they have been dated to approximately sixty-eight million years ago (Maastrichtian faunal stage of the Late Cretaceous).

European Azhdarchid Pterosaur

Scientists were able to excavate a number of associated cervical vertebrae (neck bones) plus elements from the long digit that acted as a support for the pterosaur’s wing. The strata of the Sebeş-Glod region have provided palaeontologists with a wealth of vertebrate fossils including crocodilians, turtles, lizards plus a number of primitive mammals. Some of these small creatures may well have been the prey of this new flying reptile species which has been named as Eurazhdarcho langendorfensis, the genus name comes from a combination of Europe and the azhdarchid pterosaur group. The specific name relates to Langendorf, the name of the town of Lancrǎm in the native dialect of the ethnic German minority population of Romania.

A Diagram showing the Fossil Bones Found of Eurazhdarcho langendorfensis

Illustration credit: Mark Witton (University of Southampton)

Eurazhdarcho langendorfensis

Although the bones have been heavily eroded and show signs of having been scavenged by crocodiles and further damaged by insect activity after burial, the fossils represent one of the most complete azhdarchid pterosaurs found in Europe to date.

Analysis of the finger bones that supported the long wing indicate that this flying reptile could fold its wings up and walk on all fours. It has been speculated that these inland pterosaurs may not have been fish-eaters like coastal pterosaurs but they may have stalked prey rather like extant Marabou Storks. The absence of any skull material prevents the research team from being able to gain a more complete understanding of the diet of these animals, however, it is very likely that E. langendorfensis had a large, toothless beak.

Dr Darren Naish (University of Southampton), one of the research team members responsible for the study which has been published in the academic journal Public Library of Science (PloS One) commented:

“With a three-metre wingspan, Eurazhdarcho would have been large, but not gigantic. This is true of many of the animals so far discovered in Romania; they were often unusually small compared to their relatives elsewhere.”

During the Late Cretaceous, much of this part of southern Europe was covered by a warm, shallow sea. There were a number of small islands, an archipelago or island chain and the strata in Transylvania formed one such island. The dinosaur fauna seemed to have adapted to the limited resources on these islands and many species show a degree of dwarfism, including the tiny, pony-sized titanosaur known as Magyarosaurus.

As pterosaurs could fly, they were not effectively marooned on the small islands and some azhdarchid fossils discovered in the late 1990s indicate that some species were giants with wingspans in excess of ten metres.

The discovery of this new genus of pterosaur, much smaller than the giants such as Hatzegopteryx thambema, suggest that as with other azhdarchid pterosaur discoveries elsewhere in the world, large pterosaurs co-existed with smaller species sharing the same environment. This suggests that even on these poorly resourced island chains, different types of pterosaur were hunting different types of prey in the same region at the same time, indicating that the food chain in this part of the world during the Late Cretaceous was more complicated than previously thought.

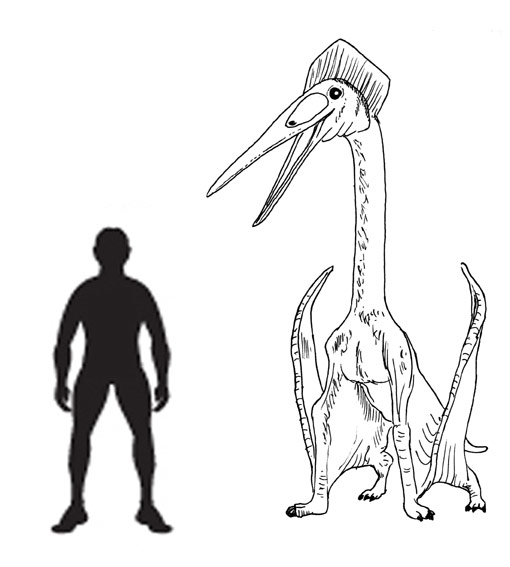

A Scale Drawing of the Giant Hateg Pterosaur H. thambema

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

For models and figures of pterosaurs: Pterosaur Models and Dinosaurs (CollectA Prehistoric Life).

Senior Lecturer in Vertebrate Palaeontology at the University of Southampton, Dr Gareth Dyke reflected on the potential feeding habits of these types of flying reptiles.

He stated:

“Experts have argued for years over the lifestyle and behaviour of azhdarchids. It has been suggested that they grabbed prey from the water while in flight, that they patrolled wetlands and hunted in a heron or stork-like fashion, or that they were like gigantic sandpipers, hunting by pushing their long bills into mud.”

The research team are hopeful that more pterosaur remains will be found in the Transylvanian Basin, including skull material which might yield further evidence regarding the dietary behaviour of the Late Cretaceous reptiles.

The scientific paper: “A New Azhdarchid Pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous of the Transylvanian Basin, Romania: Implications for Azhdarchid Diversity and Distribution” by Mátyás Vremir, Alexander W. A. Kellner, Darren Naish and Gareth J. Dyke published in PLoS One.

Were the pterosaurs able to actually fly by flapping their wings, or did they just glide? If gliders only, how did they get themselves safely airborne again after grabbing a fish at the surface of a body of water? I’d love to have an answer about this!

Pterosaurs like birds, when the opportunity arose they would glide as this is an energy efficient form of travel. The larger Pterosaurs such as the Azhdarchidae were very capable gliders but as far as scientists can tell, these flying reptiles were very able fliers and they were capable of powered flight. They did flap their wings and to all extents and purposes these animals were very accomplished fliers.