Eggshell Geochemistry Suggests Endothermy Deeply Rooted in the Dinosauria

The puzzle of dinosaur metabolism has been a subject of debate amongst vertebrate palaeontologists for a very long time. Numerous studies have been published, drawing on a variety of research methods and lines of enquiry to determine whether the non-avian dinosaurs were warm-blooded like their avian (bird) relatives, or whether they were cold-blooded like today’s crocodilians. A study published in the journal “Science Advances”, one that looked at the geophysical and chemical properties of dinosaur eggshell, has concluded that non-avian dinosaurs had the ability to metabolically raise their temperatures above their environment – in essence they were endothermic, that is to say “warm-blooded”.

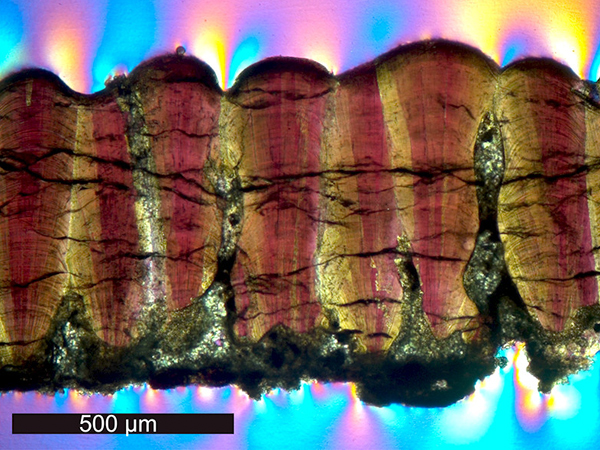

A Thin Cross-section of Fossilised Eggshell Viewed under Cross-polarising Light to Reveal Internal Structure

Picture credit: Robin Dawson/University of Yale

Non-avian Dinosaurs were they Cold-blooded or Warm-blooded?

The terms cold-blooded and warm-blooded are found frequently in articles about dinosaurs. These terms are very misleading and have been disregarded for a long time by most of the scientific community. For example, most lizards, regarded as cold-blooded, actually maintain a surprisingly high body temperature in their normal environment during the daytime. Internal body temperatures around 42 degrees Celsius have been recorded in some species, much higher than the normal 37˚ Celsius associated with our own “warm-blooded” species.

In simple terms, cold-blooded animals (ectotherms), are largely unable to regulate their own body temperature without the assistance of external sources. Lizards bask in the early morning sun to warm up and then during the heat of the day, they seek shade to help them to keep cool. In contrast, “warm-blooded” organisms such as mammals and birds (endotherms), are able to maintain a body temperature that is higher than the temperature of the environment. They can generate their own body heat. This heat comes from the animal’s metabolism, the chemical reactions that take place in the body (although there are other methods of keeping cool and warming up).

The Debate over Endothermic or Ectothermic Dinosaurs

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Understanding the Metabolism – So What?

Understanding the metabolism of a long extinct group of animals such as the non-avian members of the Dinosauria, can provide valuable insight into all sorts of areas, such as energy requirements, food consumption, behavioural traits and activity levels. It can also help scientists to understand how extinct animals adapted to a wide range of environments, such as non-avian dinosaurs being found at high latitudes. Dinosaur fossils being discovered in Antarctica for example.

In this newly published study, the researchers used a technique known as clumped isotope palaeothermometry. It is based on the fact that the ordering of oxygen and carbon atoms in a fossil eggshell are determined by temperature. Once the order of the atoms has been plotted, the scientists can calculate the internal body temperature of the egg-layer.

Based on this analysis, the research team were able to demonstrate that potentially, the three major clades of dinosaurs, Ornithischia, Sauropodomorpha and Theropoda, were characterised by warm body temperatures.

Non-avian Dinosaurs Characterised by Warm Body Temperatures

Commenting on the significance of this study, lead author of the research Robin Dawson, who conducted the research while she was a doctoral student in geology and geophysics at Yale University stated:

“Dinosaurs sit at an evolutionary point between birds, which are warm-blooded, and reptiles, which are cold-blooded. Our results suggest that all major groups of dinosaurs had warmer body temperatures than their environment.”

Eggshell ascribed to a troodontid (theropod) tested at 38˚, 27˚, and 28˚ Celsius (100.4, 80.6, and 82.4 degrees Fahrenheit). Eggshells from the large, duck-billed dinosaur Maiasaura (an ornithischian dinosaur), yielded a temperature of 44˚ Celsius (111.2 degrees Fahrenheit). Both the troodontid and Maiasaura eggshells were collected from Alberta, Canada.

Studying Fossil Eggshells

In addition, the fossilised eggs associated with the oospecies Megaloolithus from the Hateg Formation of Romania tested at 36˚ Celsius (96.8 degrees Fahrenheit). The taxonomy of the Romanian material remains uncertain. The eggshells could represent the dwarf titanosaur Magyarosaurus, the much larger titanosaur Paludititan or indeed, the dwarf hadrosauroid Telmatosaurus. If this fossil material does represent a sauropodomorph, then these results could suggest that metabolically controlled thermoregulation was the ancestral condition for the Dinosauria.

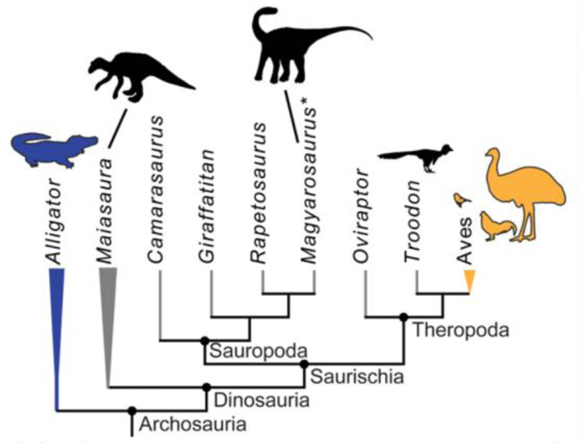

The Taxonomic Relationships of the Taxa Involved in the Study

Picture credit: Science Advances

The picture (above), shows living ectotherms in blue, whilst extant endotherms (birds) are shown in orange. The Maiasaura silhouette represents the major dinosaurian subclade Ornithischia. The asterisk (*) indicates the uncertainty over the taxonomy of the oospecies Megaloolithus, but the fossil eggshells could represent the dwarf sauropod Magyarosaurus. The troodontid material is assigned to the Theropoda.

Fossil Shells Compared with Fossil Eggshells

The researchers conducted the same analysis on cold-blooded invertebrate shell fossils (molluscs) from the same locations as the dinosaur eggshells. This helped the scientists determine the temperature of the local environment — and whether dinosaur body temperatures were higher or lower.

Dawson, now a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, explained that the troodontid samples were as much as 10˚ Celsius (50 degrees Fahrenheit), warmer than their environment, the Maiasaura samples were 15˚ Celsius warmer (59 degrees Fahrenheit) and the Megaloolithus samples were 3 to 6˚ Celsius (37.4-42.8 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer.

She added:

“What we found indicates that the ability to metabolically raise their temperatures above the environment was an early, evolved trait for dinosaurs.”

Other Implications

This new research may have other implications as well. For instance, the study shows that a dinosaur’s body size and growth rate may not necessarily be a good indicator of body temperature. The researchers also stated that their findings might add to the ongoing discussion about the role of feathers in early bird evolution. Dense coats of feathers may have evolved to help insulate the bodies of dinosaurs, secondary functions such as for use in visual displays or as part of adaptations towards powered flight occurred later.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a press release from Yale University in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Eggshell geochemistry reveals ancestral metabolic thermoregulation in Dinosauria” by Robin R. Dawson, Daniel J. Field, Pincelli M. Hull, Darla K. Zelenitsky, François Therrien and Hagit P. Affek published in the journal Science Advances.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

This is nonsense. If an object is 10 degrees Celsius (50 degrees Fahrenheit) and I raise it’s temperature by 10 degrees Celsius, I am actually raising it to 20 degrees Celsius, which is 68 degrees Fahrenheit i.e. I am raising the temperature by 18 degrees F. If only I had a £ or $ for every time I saw that mistake.

Thank you for your comment, we can only refer you directly to the media release from Yale University at this link: https://news.yale.edu/2020/02/14/were-dinosaurs-warm-blooded-their-eggshells-say-yes our team members checked the transcript carefully and we do seem to have reproduced this data accurately from the Yale University source. Further information and perhaps clarification can be found by reference to the actual scientific paper, details of which have been published by Everything Dinosaur team members at the end of our article.